Throughout your academic career, from graduate studies onward, you will regularly need to give presentations of your work to various audiences. Everything from in-class presentations, conference presentations, to your thesis defense, seminars and colloquia.

I’ve sat through too many bad talks to count. In fact, I would say that only one out of every four or five talks that I’ve sat through has been a presentation I would consider “good” (and not just “good” because the topic was directly related to my own research, but good because it was engaging and informative).

There are various qualities that make a “good” presentation, some of which are easy to quantify. Below I give a list of qualities that I’ve found tend to make good (or, conversely, bad) presentations.

Don’t go overtime. Don’t go overtime. DON’T GO OVERTIME!

For starters, in the easily quantifiable category, IF YOU WANT TO GIVE A BAD PRESENTATION, GO OVERTIME. There is pretty much no one, in any academic audience, ever, that said “YAY!!! The speaker is going overtime!!!”.

In a presentation, it is a good general rule of thumb to budget three to five minutes per slide (depending on how full of information they are). Stick that that budget. Once you have your slides prepared, read through them slowly, giving your presentation out loud or in your head, timing yourself.

At the beginning, show a slide or two (or three or four or five) motivating your work

In a past module, I discussed the difference between motivation and objective, and why both are needed to form a well-posed research question. Far too often, researchers fail to properly state the motivation for their work, and move right on to describing their objective. The motivation is the statement of why anyone should care about the analysis. For instance, influenza kills hundreds of thousands of people each year. That’s a good motivation to do studies to try to determine how to control it. An objective related to that motivation might be a modeling study of optimal control strategies.

In too many talks, the speaker jumps right in to describing their analysis, under the assumption that everyone in the audience is aware of why it might be motivated (if indeed the researcher has thought about motivation at all). Always have a slide or two describing the background to the analysis and why people should care about the research topic. You should also give a brief overview of what’s been done before (if anything), and mention how what you’re doing is novel.

Include more pictures, less text

Audience members tend to vary in their research abilities (particularly, for instance, at conferences or departmental seminars where there is a mix of students and faculty). As you are describing your work, you need to be aware that a significant fraction of the audience is likely to get lost at one or more points during your talk. I’m not ashamed to say I fairly frequently have no idea what speakers are talking about during at least some point in their talk. I usually kind of get the gist in most cases, but not infrequently the speaker truly loses me.

The better talks I’ve seen ease the pain of getting temporarily lost by including lots of graphics in the presentation, instead of having slides stuffed with text or equations. A picture or a figure can convey much more information than a paragraph of text. The pictures don’t even need to be that full of information in order to make the talk much more interesting than it would be without pictures. For instance, I could tell you that in summer 2014 during the Ebola epidemic in West Africa, Guinea, Sierra Leone, and Liberia instituted mass quarantine measures of entire villages and regions that they used military to enforce. That statement has greater impact when accompanied by a photo of what these blockades looked like:

The photo conveys the serious nature of this attempted measure to slow the spread of the virus. The quarantine was so strictly enforced, riots broke out due to poor food supply and crowding (in a talk on the subject I might include a picture of some of those riots too). As it turns out, these conditions actually may have made the outbreak worse.

There are all kinds of stock pictures you can download from the web. Google is your friend in finding them. It is good form to credit the source in your talks.

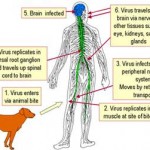

Talking about your modeling work in rabies? Show a picture of a rabid dog. A map of the most affected areas. A picture of the virus. A picture describing the transmission cycle in the wild. A picture depicting the primary symptoms, and/or describing the course of the disease, etc etc.

Talking about your work modeling narcotics crime? Show a picture of drug dealers, and/or common street drugs. Incarcerations? Show people in a prison. Treatment programs? Show a picture of people in a twelve step meeting. Show the plot of the changes in the incarceration rates over time, etc etc.

Pictures give the audience something to look at while you talk. You should know what you are going to talk about on each slide without having to have a bunch of text there to guide you. The pictures themselves should be enough of a prompt for you, and if they aren’t, you need to work on that!

Including videos in your presentations is also a very nice touch, when appropriate.

Don’t read from note cards, or from the text on your slides

Reading from notes makes for a terrible presentation that utterly fails to engage with the audience. Similarly, don’t pop up a slide with text on it, and read the text verbatim to the audience. During your presentation, you need to be looking audience members in the eye, and move your eyes around the room as you speak, engaging different audience members with your eyes throughout the talk.

Instead of using notes, have visuals and/or bullet points on your slides that will remind you of the points you want to hit on that slide (while also engaging the audience by giving them something to look at, in the case of visuals). Run through your presentation in your head several times before the day you have to give the talk, and try to memorize not so much exactly what you’ll say, but the points you will hit with each slide.

If you inadvertently forget to hit a point or two on a slide, your audience likely won’t even notice. If it was something relatively important, it may come up during the question period, in which case you can say something like “Oh yes… thanks for that question… I meant to talk about that on this slide (and then flip back to that slide)”.

Have backup slides

You don’t need to present your analysis in all its excruciating detail to get your point across about what you did and how you did it. However, there may be people in the audience who are interested in the fine details. A good idea is to very briefly flash a slide with the gory details, and say during your talk something like “here are the fine details… if you have questions about it, you can ask me after the talk.” This has two advantages. A) you have the slide(s) available with all the fine details, and B) you’ve given the audience members something to ask about in the question period that you know you already know the answer to.

At the end of most of my talks (if I’m using PowerPoint, which I do less and less these days in favour of using this website), I usually have what I call “backup slides” that I don’t show during the main talk. I try to anticipate what questions audience members might have, and I create slides to answer those questions. Often I don’t end up using them, but sometimes I do, and I’m grateful I took the time to make them. If the talk is your thesis defense, or a seminar or colloquium you are giving as part of a job interview, having backup slides like this can leave the strong impression with the audience that you really know what you’re doing!

Know your audience

At a conference, it is a safe bet that your audience will be a mix of people at various stages of academia. You want to present material that engages more senior people, without losing the junior people too often. Interestingly, people often assume that even senior people in a field are aware of the details of different methodologies. As an example, when I was a grad student in physics, a classification method called the Fisher Discriminant came somewhat into vogue in the field. Various papers used it in their analyses, and in conference talks people would mention it as if everyone knew how it was used.

As a grad student, I had to give a talk at a conference on one of those analyses, and I realized I didn’t really know exactly how the method worked (in particle physics it is not uncommon to have to give conference talks on analyses you didn’t actually do!). So I researched it, and spent a couple slides in my talk talking about it. It was well received, because it turned out that most senior people in the field (let alone the junior ones) were only vaguely aware (if that) of the details of the method.

So, if your analysis includes methodology that, for instance, you learned in a specialized graduate course, or while working with your advisor, it may well be worth spending a slide or two describing that methodology instead of assuming everyone knows about it. You don’t need to go into deep detail. Just enough to leave people with a warm fuzzy feeling that “Aha! Now I know how that method works!”.

While I am on this topic, I should mention the difference between a seminar and a colloquium. Some departments do not make a distinction, others do. In the ones that do, colloquia are talks intended at a general audience. In a departmental colloquium in mathematics, for instance, the talk is intended for all mathematicians, not just applied mathematicians and/or just mathematical modelers. In a colloquium, you are not only presenting your work, but also representing the field itself. You need to give examples as to why mathematical modeling is important. Don’t assume that someone from topology (for example) will have any idea what a modeler in the life and social sciences does, or why what we do is important. Think of a colloquium as a TED Talk. Talks you give as part of a faculty job interview are often along the lines of a colloquium, even if they are not referred to as such.

Seminars, on the other hand, when a distinction is made between the two, are generally aimed at people within your specific field, or a related field. With seminars you can go into greater detail regarding your analysis than you can in a colloquium. Talks you give as part of a postdoctoral job interview are usually more along the lines of a seminar, rather than a colloquium.

It helps to be amusing

Some people are better at being amusing during talks than others. If you can insert a joke, pun, funny picture, etc at a natural point in your talk, I encourage you to do so. Some of the best professors I ever had were very good at both conveying information and being really funny about it at the same time. It was a pleasure to attend their lectures.

An ASU study has shown that students felt they learned better in courses where the professors were funny.

Giving invited talks at universities

If you are visiting another university either as an invited speaker or because you are there for a job interview for a postdoc or faculty position (and are giving a seminar associated with that), you will usually have a faculty host for the visit, and it will usually be that host who will introduce your seminar talk.

The host generally will strive to make you feel comfortable, arrange the schedule of people you will meet with, arrange for desk space for you during your stay, take you out to lunch and/or dinner, and will usually (but not always) arrange things such that you will have half an hour to an hour before your seminar to go over your slides. Your host will often ask you some things about yourself, like your educational background, for example, such that they can introduce you right before your talk. The host for your seminar talk will usually also ask a question after your talk (for politeness sake, at the very least).

Signs that you’ve given a good talk (or a bad talk)

The best sign that you’ve likely given a good talk that engaged the audience is several people raising their hands immediately after you finish. I’ve had students think in their first big talk that so many hands being raised means that they must have given a bad talk because there were so many questions about it… not at all. It usually means that your talk engaged the audience right to the end, and they want further information and were interested in the topic.

The possible exception to this is if audience members queue up to bash your talk, either because you showed an ignorance of existing key research on the topic, or your analysis methods were deeply flawed. Getting one such person critiquing your talk can sometimes happen simply because jerks exist in the world… however, if one or more people critique it with very valid comments, that is a sign that there are flaws in your research that need to be addressed before you take it public again. Keep an open mind when it comes to criticism! If you get defensive, it is counter-productive to your development as a researcher because some good advice can sometimes be conveyed rudely by colleagues… but that doesn’t mean it wasn’t good advice. Junior researchers should always discuss the negative comments they got on their talks with their mentors to help assess the validity of the feedback. Importantly: never get defensive, never take it personally, and always politely thank people for their input, even if you don’t like it.

The worst is when you finish a talk, and you or your host says “any questions”, and there is nothing but the sound of crickets in the room. Out of politeness, if you have a host, they will almost always ask one question. But if that is the only question you get, that is a sign you really failed to engage the audience. But it sometimes can be hard to gauge why. Several things might have happened to cause this… you may have failed to motivate the topic, you may have used too much jargon, you may have seriously misjudged the skill set of your audience (either thinking they were far more, or far less, experienced in your topic than they actually were), and/or you may have put far too many very technical slides in your talk that lost your audience early on (and once you lose their attention, it is very difficult to get it back). Before you take that presentation public again, seek help from a more senior mentor on ways that you might potentially improve it.

What you, as an audience member, can do to make the talk better

Some of the best advice I’ve ever gotten was from one of my graduate mentors, who said to me (paraphrased) “You’re not stupid… if you aren’t understanding something, then other people in the room aren’t either, so never be afraid to ask questions.” The man who made that statement was one of the smartest people I’ve ever met… if he’s unafraid to admit he gets lost during talks, the rest of us should be brave enough to admit it too!

Once you have your undergraduate degree, and especially once you have your graduate degree, you have your license to think. There is nothing any more special about me compared to you when it comes to my ability to understand content being presented. If you aren’t understanding something, it is very likely there are several other people in the room in the same boat. It is the speaker’s fault for not comprehensibly conveying the information, not yours for not understanding it.

ASK QUESTIONS!

Here is a page that gives some examples of more-or-less generic questions you might ask at a seminar (or when you review a paper, for that matter). Some of the questions are quite reasonable, for example asking questions in sections (2) and (5) of that document. However, the author of the document appears to revel in being a jerk to seminar speakers, so I really don’t recommend the nasty tone, nor some of the obviously random questions that he seems to enthusiastically suggest. Also, it irritates me that the author refers to all seminar speakers as male… the guy appears to be a total jackass in more ways than one. Anyway:

- (2) Systematic questions. These questions can involve asking things like the sensitivity of the model results to initial conditions. Or why was one model chosen over another? Why was a particular fitting method used (if data are involved)? How sensitive are the model results to the parameter assumptions?

- (5) What is potential future work?

This document is a primer for science journalists to guide them in asking questions about new scientific studies. In particular, suggestions 6, 7, and 8 can for the basis of questions you might ask at a seminar, or when reviewing a paper:

- 6. How generalizable are the results? if the researcher, for example, fit an SIR model to an influenza epidemic, are the results of that analysis expected to be applicable to any flu epidemic, anywhere in the world? If not, why not? And also, if not, what then is the general conclusion that can be obtained from the analysis?

- 7. What are the limitations of the study?

- 8. What conclusions do similar studies draw?

There are of course questions you can ask about plots, if they are poorly labelled, or confusing, or about the model equations if some of the parameters or variables are not defined.

I usually word most questions I ask in a seminar along the lines of “Perhaps I missed it when you were talking, but could you explain blah blah blah a little further? I don’t think I understand the figure you had on slide 21”. Wording questions in this way is less confrontational, and more polite than just saying you didn’t understand something.