Introduction

[This post is the first in a series on archaeoastronomy using open source software]

One of my academic hobbies is archaeoastronomy, which includes the study of how ancient peoples observed the sky. As I will describe in a series of posts on this topic, I pursue my hobby with the use of free data and free software tools like Google Earth and the pyephem astronomical ephemeris calculation library, written in the Python programming language.

Wikipedia gives a good overview of archaeoastronomy:

Archaeoastronomy uses a variety of methods to uncover evidence of past practices including archaeology, anthropology, astronomy, statistics and probability, and history. Because themnse methods are diverse and use data from such different sources, the problem of integrating them into a coherent argument has been a long-term issue for archaeoastronomers.[4] Archaeoastronomy fills complementary niches in landscape archaeology and Archaeocryptography and or cognitive archaeology. Material evidence and its connection to the sky can reveal how a wider landscape can be integrated into beliefs about the cycles of nature, such as Mayan astronomy and its relationship with agriculture.[5] Other examples which have brought together ideas of cognition and landscape include studies of the cosmic order embedded in the roads of settlements.[6][7]

Archaeoastronomy can be applied to all cultures and all time periods. The meanings of the sky vary from culture to culture; nevertheless there are scientific methods which can be applied across cultures when examining ancient beliefs.[8] It is perhaps the need to balance the social and scientific aspects of archaeoastronomy which led Clive Ruggles to describe it as: “…[A] field with academic work of high quality at one end but uncontrolled speculation bordering on lunacy at the other.”[9]

The last comment in that passage speaks truth; archaeoastronomy sometimes tends to get little respect in the hard sciences due to the unfortunate prevalence of woo woo “science” where astronomical alignments in man made structures or geographic features are claimed to be created by aliens or other unknown “advanced races” not related to the actual people living in the region at the time.

Particularly in the case of structures created by native aboriginal peoples, I find offensive the assertion that the structures could not possibly have been made by those peoples.

Perhaps partially because the prevalence of woo (and the negative cast it puts on the field as a respectable academic pursuit), few people seem to be active quantitative practitioners of the field anymore. The heyday of the field was in the 1970’s and 1980’s, with practitioners such as Professors Anthony Aveni and Gerald Hawkins producing many seminal publications. Remarkably few publications have been produced in the field in the last two decades, despite the many subsequent advances in computational tools that can aid in archaeoastronomical research. Some other prominent practitioners of archaeoastronomy and/or researchers of megalithic monuments are Clive Ruggles (still active), Aubrey Burl, Alexander Thom (proponent of the “megalithic yard“, which unfortunately has almost as much woo associated with it as archaeoastronomy), Norman Lockyer, and J McKim Malville (also still active).

In addition to the woo woo, there is also the problem that some amateur (and even professional) archaeologists have claimed astronomical alignments to be definitively present at archaeological sites that have literally thousands of potential lines that could reasonably be drawn to connect features at the site; they pick one or two that happen to be aligned with some phenomenon like summer or winter solstice Sun rise, and claim proof that the site was used for sky-watching purposes. It doesn’t take much background in statistics to realize that in such a site the chances of getting an alignment with some astronomical phenomenon by mere random chance is quite high. Some previous assertions of astronomical alignments of the Nazca lines are an excellent example of “cherry picked data” studies that have since been debunked with more rigorous statistical analyses (for a good overview, see a paper by Gerald Hawkins on this topic, here, in which he discusses studies of possible astronomical alignments of the Nazca lines, sun/moon alignments at Stonehenge, etc).

As an aside, I’ll note here that the Nazca lines are in general the object of many woo woo “theories”, including theories that they must have been built by aliens as landing strips for their aircraft (yes, really). The idea that a collection of lines like the one in this picture were intended as an astronomical observatory seems almost sane in comparison to some of the other theories floating around out there.

It seems that we humans love to try to make sense of things by consciously or unconsciously searching for patterns, sometimes coming to the erroneous conclusion that deliberate patterns are evident, even when they aren’t. Another problem is that proponents of woo start with a completely different “null hypothesis” that they want to test by their analysis of a site. For instance, when I analyze archaeological sites, my null hypothesis is that the site was not used as an astronomical observatory. Unless I find statistically strong evidence that it was, I conclude it wasn’t. However, proponents of woo usually start with the null hypothesis that the site was used as an observatory. As long as they find at least one alignment of the site to the rise or set of a celestial body, they conclude that the site was used as an observatory. Their stance is that it is up to the skeptic to prove that alignment wasn’t to that celestial body in order to prove that the site wasn’t an observatory. (However, I should note here sometimes it is in fact easy to prove them wrong; in cases where I’ve been able to use satellite images to check purported alignments at ancient sites, about half the time they don’t pan out… the building(s) don’t point in the precise direction the researcher said they do.)

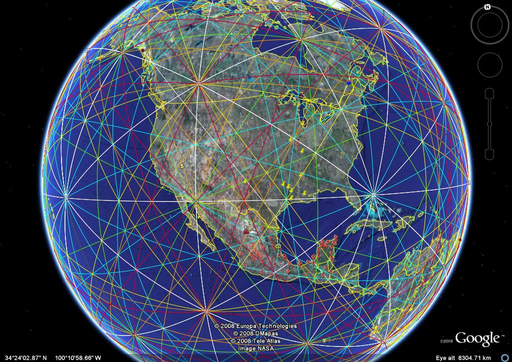

Another example of woo are ley lines, mystical lines said to connect key features on the landscape and monuments, with “electro-magnetic energy” powerful enough to cause mass die offs of birds and frogs (no, I’m not making this up).

Other, more quantitative, researchers have pointed out that you can take a random bunch of dots, and get quite a few lines apparently connecting them just by mere random chance. For instance, here are 80 4-point “ley lines” going through 137 random points (as an aside, how many of those lines do you think might be associated with the rise or set direction of some star?)

There is also a lot of woo associated with the Great Pyramids at Giza (and maybe Stonehenge). As another aside, Stonehenge is another good example of a site with literally hundreds of lines that can be drawn to connect the various sarsens, trilithons, Y and Z holes, aubrey holes, and heel stone. A proper assessment of the use of Stonehenge as a comprehensive astronomical observatory would require examining all possible alignments of these stones, and assessing the probability of observing apparent solstice, lunar, and other astronomical alignments by mere random chance. This has yet to be done.

My research interests in archaeoastronomy are centered on exactly this topic; assessing the probability that a particular archaeological site was used as an observatory. In the approach I present here, I consider all potential alignments of key site features lining up wall intersections and/or posts or stones (let’s call these “datum points”). Let’s call the lines connecting the datum points the “site lines” (which also may be “sight lines” to points on the horizon where important celestial bodies rise or set).

I also consider the rise and set azimuths (degrees from North on the horizon) of bright stars, and the extreme north and south setting points of sun and the moon. Call these the “proposed astronomical alignments”. Clearly, if I have many site lines and look at a small subset of the proposed astronomical alignments (like, for instance, the summer solstice), the probability of getting a matched alignment by mere random chance is quite high. Similarly, if we choose just a couple of the site lines and try to match them to some of the many potential astronomical alignments, the probability of getting a matched alignment by mere random chance is also quite high. But if we take all the site alignments, and all the potential astronomical alignments and try to match them, the true hallmark of an ancient “observatory” would be a site that produced a large fraction of site alignments matched to astronomical objects, and a large fraction of the astronomical objects matched to site alignments (note that one does not necessarily imply the other!).

In addition, by creating “synthetic” sites with similar numbers of datum points but randomly positioned over the area of the site, we can examine the probability of obtaining by mere random chance the observed number of site alignments to astronomical objects. We can also create a “synthetic” sky with the rise and set points of synthetic astronomical objects randomly interspersed on the horizon to examine the probability of obtaining by mere random chance the observed number of astronomical objects that appear to be aligned with the site lines. I will be describing how to do all of this in various posts to follow on this topic.

There have been criticisms, particularly coming from the field of cultural anthropology, of the purely quantitative approach I present here to determine the statistical probability that a particular archaeological site was used as an observatory. Some have stated (for instance, here) that such quantitative information is simplistic and next to useless without explanation of why ancient peoples wanted to mark the solstice, rise and set points of certain stars, etc. While I agree that knowing why they might have wanted to follow the patterns of certain astronomical objects is important for understanding the culture, for all practical purposes in many ancient pre-historic cultures no one has survived to present day with orally passed-down narratives to provide us with this information; to state that the knowledge of what ancient societies may likely have being observing is useless without knowing why, is, in my opinion, a somewhat narrow attitude about what does, and does not, advance knowledge about those societies.